Blog

Coming soon: Reflections on black hole physics, quantum gravity, and the philosophy of time.

Some good reads for those aspiring to become theoretical physicists

Here are some good references to read online for those interested in becoming good theoretical physicists. I will keep updating this list as I find more. They are not in any particular order.

- How to be a good theoretical physicist by Gerard t'Hooft : Gerard 't Hooft is a Dutch theoretical physicist who shared the 1999 Nobel Prize in Physics with his advisor Martinus J. G. Veltman for elucidating the quantum structure of electroweak interactions . He shares a straight forward perspective on how to be a good theoretical physicist. It is an ambitious goal and an inspiring read. I have found myself reading it from time to time.

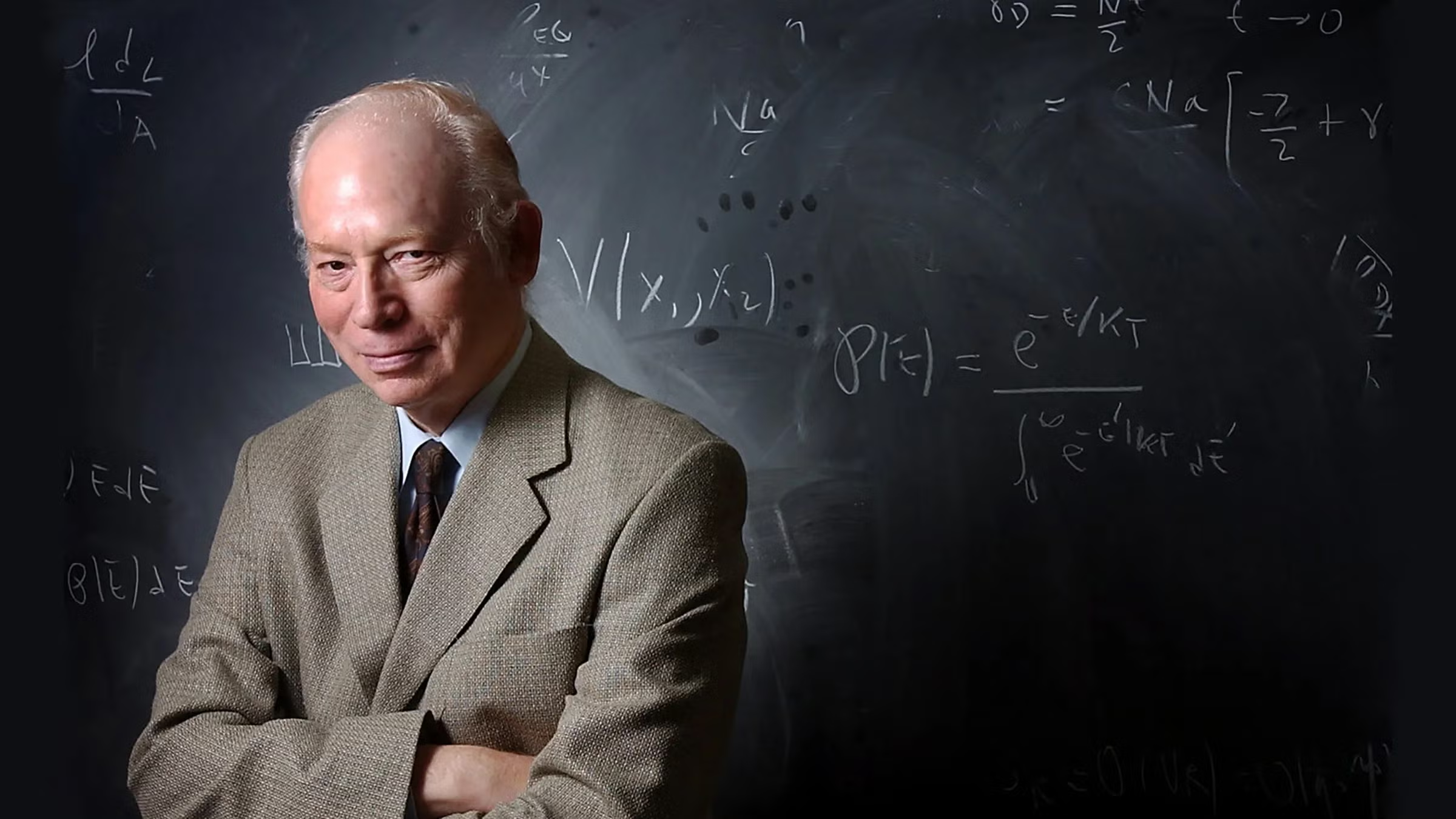

Steven Weinberg's Four Golden Lessons

Weinberg's advice to students

Steven Weinberg gave a commencement talk at the Science Convocation at McGill University in June 2003. Below I list the four lessons Weinberg gave to the students. The complete essay can be found at Four golden lessons.

- No one knows everything, and

you don’t have to.

"How could I do anything without knowing everything that had already been done? Fortunately, in my first year of graduate school, I had the good luck to fall into the hands of senior physicists who insisted, over my anxious objections, that I must start doing research, and pick up what I needed to know as I went along. It was sink or swim. To my surprise, I found that this works. I managed to get a quick PhD — though when I got it I knew almost nothing about physics. But I did learn one big thing: that no one knows everything, and you don’t have to."

- While you are swimming and not sinking you

should aim for rough water

"When I was teaching at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the late 1960s, a student told me that he wanted to go into general relativity rather than the area I was working on, elementary particle physics, because the principles of the former were well known, while the latter seemed like a mess to him. It struck me that he had just given a perfectly good reason for doing the opposite.My advice is to go for the messes — that’s where the action is."

- Forgive yourself for

wasting time.

"My third piece of advice is probably the hardest to take. It is to forgive yourself for wasting time. As you will never be sure which are the right problems to work on, most of the time that you spend in the laboratory or at your desk will be wasted. If you want to be creative, then you will have to get used to spending most of your time not being creative, to being becalmed on the ocean of scientific knowledge."

- Finally, learn something about the history

of science, or at a minimum the history of your

own branch of science.

"The history of science can make your work seem more worthwhile to you. As a scientist, you’re probably not going to get rich. Your friends and relatives probably won’t understand what you’re doing. And if you work in a field like elementary particle physics, you won’t even have the satisfaction of doing something that is immediately useful. But you can get great satisfaction by recognizing that your work in science is a part of history."

Steven Weinberg received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1979 for his contributions with Abdus Salam and Sheldon Glashow to the unification of the weak force and electromagnetic interaction between elementary particles.

How do you read a scientific paper?

If I were guiding my younger self on how to read scientific papers...

If I were guiding my younger self on how to read scientific papers, I would emphasize the following three important things to make his life simpler:

- Understand the Problem and Context:

Before diving into a paper, it's crucial to have a clear understanding of the problem or topic it addresses. Familiarize yourself with the broader context in which the research is situated. Ask yourself questions like: What is the research question? Why is it important? What are the key concepts or theories involved? Read any introductory sections or background information provided in the paper to grasp the foundational knowledge and motivation behind the study.

- Critical Analysis and Note-Taking:

As you read the paper, take diligent notes and highlight key points, equations, figures, and results. It's essential to engage critically with the material. Don't just passively read; actively question and evaluate the content. Look for strengths and weaknesses in the research methodology, data analysis, and conclusions. Consider the evidence presented and whether it supports the authors' claims. Are there alternative interpretations or limitations to their approach?

- Synthesize and Connect:

After reading the paper, take time to synthesize the information you've gathered. Try to connect the paper's findings with what you already know about the subject. How does this paper fit into the larger body of literature in the field? Does it confirm or challenge existing theories? It can also be helpful to discuss the paper with peers or mentors to gain different perspectives and insights.

Take away:

- Type in the problem and clearly explain the context of the problem — why was it tackled?

- List the key concepts learned and analyze what wasn’t clear to you.

- Summarize the paper in your own words. Ask: how does this fit the broader context? Can this spark new ideas?

Remember that reading scientific papers is a skill that improves with practice, so don't be discouraged if it feels difficult at first.